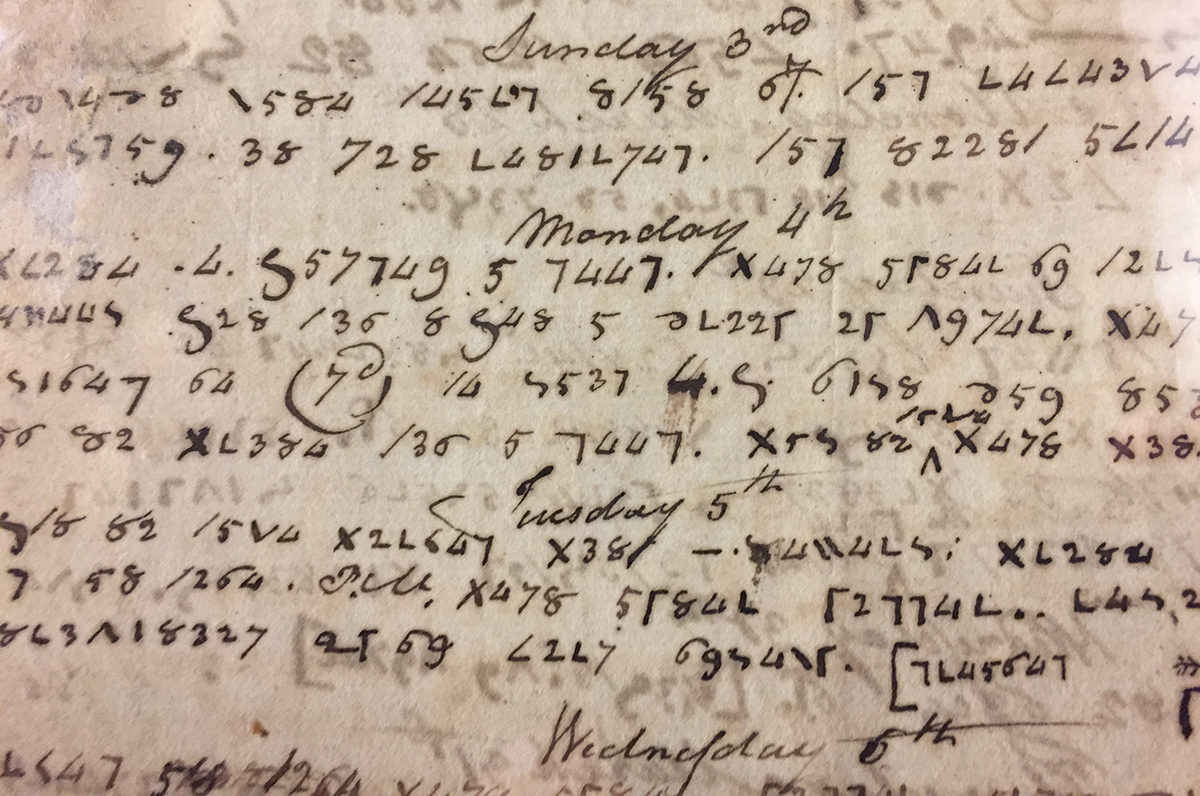

1808 diary sample

By Lauren Stepp

Long before anyone could read them, William Thomas Prestwood’s diaries were already alive with secrets.

For decades, the 19th-century Appalachian farmer filled his hand-sewn notebooks with the stuff of sin and science—astronomy, anatomy and adultery—all written in code. More than a century later, his descendant, Henderson County author Jeremy Jones, stumbled upon the mystery while digging through a box of family relics.

“I’d gone to my grandma’s to look for old family photographs to include in my first book, Bearwallow, but as I sifted through the box, Grandma reached in and fished out an old newspaper clipping she’d saved but apparently forgotten,” Jones recalls. “It told of the discovery and decoding of the diaries—and of the diarist’s many recorded sexual affairs. I didn’t know I’d spend the next 10 years obsessing over those diaries then, though.”

“I’d gone to my grandma’s to look for old family photographs to include in my first book, Bearwallow, but as I sifted through the box, Grandma reached in and fished out an old newspaper clipping she’d saved but apparently forgotten,” Jones recalls. “It told of the discovery and decoding of the diaries—and of the diarist’s many recorded sexual affairs. I didn’t know I’d spend the next 10 years obsessing over those diaries then, though.”

The notebooks first surfaced in 1975, when a man in Wadesboro, NC, uncovered a box of delicate, hand-stitched journals in a house slated for demolition. Their pages were covered in cryptic symbols, so he turned them over to a retired National Security Agency cryptanalyst. The codebreaker succeeded, revealing a startling portrait of Prestwood: a white farmer who charted eclipses, dissected rabbits and calculated planetary orbits before slipping into closets and haylofts with lovers.

“The reader is left,” the codebreaker wrote, “with the lasting impression that here in these pathetic little books is the very essence of Everyman’s life from the cradle to the grave.”

But to Jones, Prestwood was no Everyman—he was blood.

“To be honest, when I first learned about them, I saw the diaries as a curiosity,” Jones says. “I flipped through and looked for certain four-letter words and scandalous acts, but I didn’t really engage with them in any deeper way. Eventually, though, I started reading the diaries chronologically, and then the man captured there began to take shape.”

Jones’ new book, Cipher, follows Prestwood as he mines for gold, hides runaway slaves, befriends Daniel Boone’s great-nephew and raises sons destined for Gettysburg. But not every chapter of his ancestor’s life was so easy to trace.

For example, in 1838, Prestwood abruptly wrote “start army” and then went silent for two weeks. To uncover what happened during that time, Jones worked with historians at Western Carolina University and learned that Prestwood had joined a local militia tasked with rounding up Cherokee families during the Trail of Tears.

“Excavation may be a good word,” Jones says of this research process. “There was a lot of puzzling, and so it did feel akin to pulling up pieces of another life and then trying to see how they fit together.”

Through that excavation, Jones came to see history not as something distant and static but as a living force that continues to shape who we are.

“I think we owe it to our ancestors to try to learn from how they lived, even if our response is to aim to live in the opposite way,” says Jones. “I think we owe it to ourselves to closely examine the past, in all of its messiness, so that we can try to move forward into a better world.”

To learn more, visit TheJeremyBJones.com.