Preserving the Yancey County Community of Lost Cove

Home in Lost Cove. Photo courtesy of Jeff Bryant

By Lauren Stepp

As a child in eastern Tennessee, Christy Smith heard tales of a ghost town just over the state line.

“My great-grandfather would tell stories about this place called Lost Cove,” says Smith.

According to her “Old Pop,” Lost Cove sat a mile above the Nolichucky River in a remote corner of Yancey County. There, on 400 acres of loamy North Carolina soil, some 100 mountain folk scratched out a living for the better part of a century.

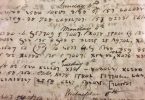

Lost Cove inhabitants. Photo courtesy of Teresa Miller Bowman

It was a wild world, said Old Pop. Neighbors cared deeply for one another and the land, yet were quick to defend illegal practices—namely illicit distilling. Lost Cove was, in essence, a place of love and lawlessness. But in the late 1950s that way of life came to an end.

With her imagination running wild, Smith set out to see this desolate settlement for herself in 1982.

“At the age of ten, I hiked into the cove,” says Smith. There, she found derelict cabins and rusting cars. The town was spiritless. But Smith could hear the forest whisper stories from bygone years, and she was ready to listen.

In the decades since then, Smith has unearthed Lost Cove’s clandestine history. Her findings were published in Lost Cove, North Carolina: Portrait of a Vanished Appalachian Community, 1864-1957 last November.

The text traces the town’s settlement back to a man named Morgan Bailey. Shortly before the Civil War, Bailey bought land in Lost Cove from a Native American. It cost him $10 and a shotgun.

After Bailey put down roots, more families followed. According to Smith, clans like the Tiptons and Millers “were determined to battle the harsh elements and live a quiet life, away from the chaos of war.”

Early inhabitants sustained themselves on row crops like corn, potatoes, cucumbers, tomatoes and green beans. For extra cash, some sold ginseng while others made hooked rugs. But the most lucrative hustle was moonshine.

As noted in a newspaper article from 1898, moonshining thrived in the settlement because of a boundary dispute between North Carolina and Tennessee. Since neither state could claim the area, revenue agents struggled to crack down on illicit distilling.

Starting in the early 1900s, moonshiners even used the railroad to distribute product. “They would send barrels down to the tracks and have it hauled,” says Smith. The liquor was so prolific that Smith’s great-grandfather nipped on the stuff.

But in the 1950s, as timber resources dried up and passenger trains stopped running, Lost Cove began to wither.

“Though families triumphed over hard times in the past, now times were different,” Smith writes. “The ability to earn income in Lost Cove began to fade.”

Desperate for jobs and higher education, inhabitants abandoned the community in droves. The last family—Velmer Bailey, his wife, and four children—gathered everything they could carry and walked out of the cove on January 1, 1958.

Today, Lost Cove is nothing more than a collection of ramshackle homes and outbuildings. But, thanks to Smith, its legacy lives on.

“Lost Cove is a testament to the self-reliance and self-sufficiency of Appalachian people,” she says. “The town’s story must be told.”