By Paula Musto

Trees. Trees. Trees. Dead ones, that is, lying prostrate across Western North Carolina, a stark reminder of the fierce storm that tore through the region last fall.

At first glance, fallen trees may seem a sad sight in our yards, along hiking trails and deep in our forests. But these dead specimens warrant another look. From tiny insects and wood-decay fungi to roosting birds and shelter-seeking mammals, seemingly barren trees are teeming with life. For some animals, their survival is directly connected to the demise of the broken trunks and scattered logs on the forest floor.

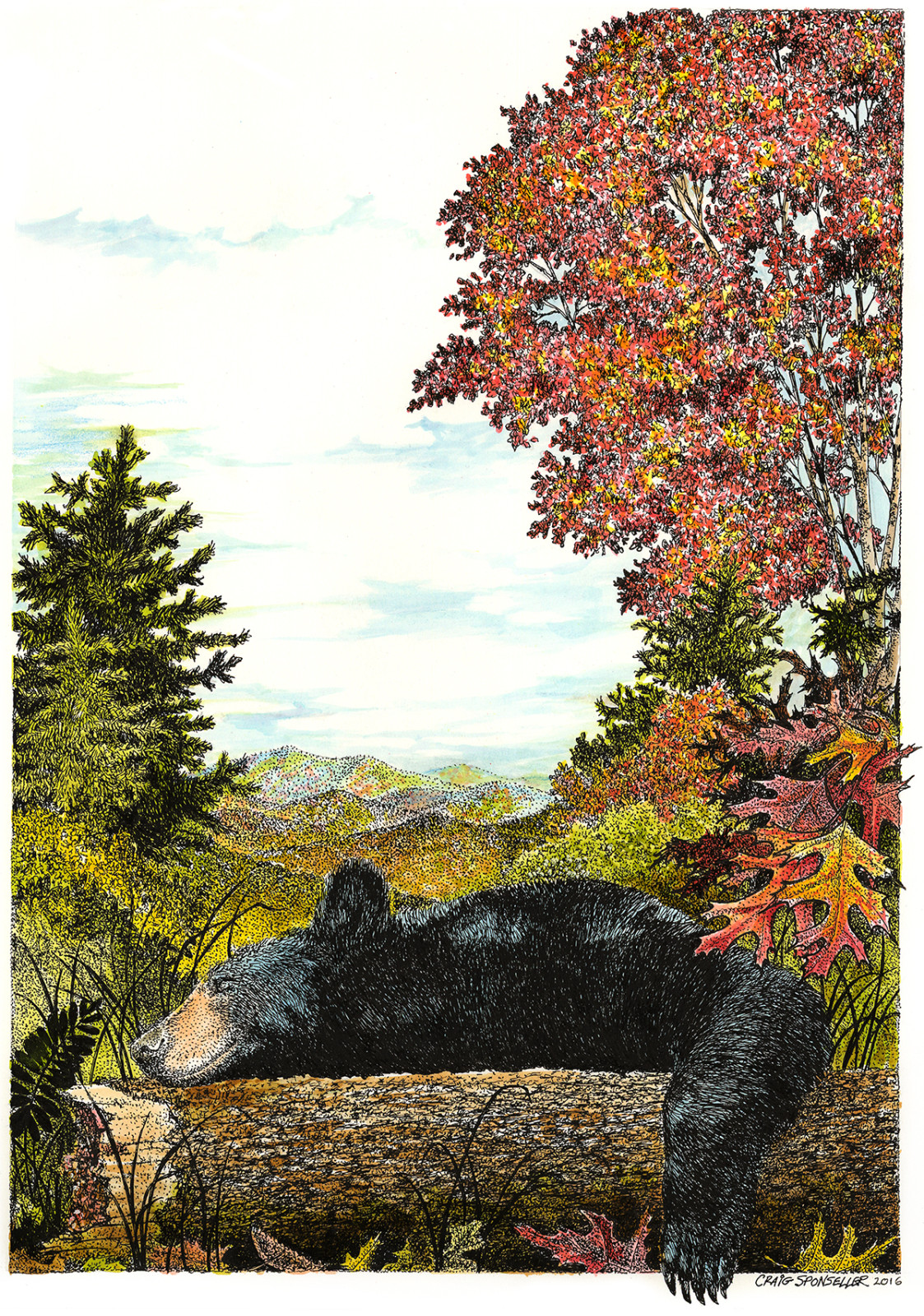

A Lazy Day in the Blue Ridge. Craig Sponseller, artist

“People often overlook that when a tree dies its role in an ecosystem does not end,” says James Fuller, a wildlife biologist and founder of the Big Asheville Science Salon, which hosted a discussion this summer on the types and number of trees that fell in the Asheville area during Hurricane Helene. “Rather, it transitions from providing the critically important ecological functions of live trees to providing the critically important ecological functions of dead trees.”

While living trees play a multitude of vital roles—including absorbing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen, essential for life—once a tree dies, important benefits continue. These include providing shelter for wildlife, supporting recycling of critical nutrients, aiding plant regeneration and lessening soil erosion.

Foresters do not know the exact number of trees lost in our region as a result of Helene’s catastrophic wind, flooding and mudslides, but estimates are in the tens of thousands. Preliminary aerial surveys by the North Carolina Forest Service identified an estimated 800,000 acres of forest moderately to severely damaged. While thousands of toppled trees blocking roadways and residential neighborhoods have been removed, this represents only a small percentage of last September’s blowdown.

So, who’s benefiting? We all know about the noisy woodpeckers who rely on wood to harvest meals. But scientists estimate that two-thirds of all wildlife species rely on downed trees during some portion of their lifecycle. Bats, for example, hide in cavities of dead trees, as do species of snakes, salamanders, frogs and a diverse collection of small mammals. Foxes and coyotes use logs for dens. Decaying wood is a major home for pollinating insects like wasps and bees. Seed-eating animals, including wild turkeys, enjoy the abundant buffet of nuts and seeds that fallen trees dispense. Moist, rotting wood supports fungi populations that provide food for insects, turtles, birds, squirrels and deer.

As with so much of nature, however, what’s beneficial depends on perspective. For humans—especially those with homes adjacent to heavily forested land—there is a heightened risk of wildfires, especially in the typically dry fall and spring months.

“There is no question that aspects of Helene’s blowdown have increased the threat of wildfires in our region,” says Steve Norman, a research ecologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Research Station who has studied fire patterns in WNC over recent centuries. “Historically, the Southern Appalachians are fire-prone. Today, risks are more complicated by Helene and development.”

Toppled trees not only leave behind leaves and branches that can increase fire intensity and spread wildfires but the remnants of large trees, now crisscrossing the forest floor, can impede fire crews when attempting to create fire lines to fight a blaze. Another long-term fire concern, Norman says, is the multitude of decaying trees that will be on the ground for decades: in the event of a drought during fire season, like the one the region experienced in 2016, smoke and smoldering wood puts the area at risk for an air-quality hazard.

“Helene was a very powerful, transformative storm,” Norman says. “We don’t have experience with this type of blowdown so far inland. Foresters, firefighters and homeowners may have to think about risks in different ways than before, and there are still a lot of things we do not understand.”

This includes what he calls a tradeoff—the removal of fallen trees as part of ongoing salvage logging operations that reduce the amount of deadwood on the forest floor. Whether and how clearing dead trees affects wildfire hazards and the viability of our forests, however, remains a topic of discussion among foresters and conservationists.

Some advocates prefer to leave dead trees untouched whenever possible unless they are a safety concern to people or property. Others, however, seek to gain commercial value from the impacted forest stands and reduce fire hazards more aggressively.

As an ecologist, Fuller says he views the dead tree question as an intersection (or maybe a collision) between ecosystem functionality (how natural habitats have evolved over millions of years) and the interests and proclivities of humans who favor manicured landscapes over ones punctuated by decaying trees.

In the wake of Hurricane Helene, foresters, wildlife ecologists and others are seeking to find a balance. It will be an issue in our region for years to come.

But the next time you walk through a forest and encounter the many relics of Helene, Fuller suggests taking a moment to consider that it’s not just crumbling debris scattered about. Take a close look; those fallen branches and tree trunks are full of life.

Paula Musto is a writer and volunteer for Appalachian Wildlife Refuge which cares for injured and orphaned wildlife. Visit AppalachianWild.com to learn more or to donate.

Love this article! so much wisdom here. I have a dogwood tree in my front yard, half of which doesn’t flower and has some decay. Nevertheless my tree is always full of squirrels, cardinals, Eastern bluejays, starlings, mourning doves, crows, robins, sparrows and a variety of other birds. A family of chipmunks is often seen at the base of the tree and once a red-tailed hawk landed in its branches. There is abundant life all around the tree: spiders and all kinds of insects and various plants that have bloomed around it. I lay wildbirdseed and blueberries in a circle around the dogwood and that is picked clean in an hour or two by the neighborhood wildlife. When neighbors have remarked, “you only have half a dogwood tree since many of its limbs have decayed!” I respond “But I have a “the dogwood-tree is half full and it doesn’t seem to mind much what the rest of it is doing.”